Will Rising Energy Prices Lead To Higher Inflation?

It happens whenever there’s a sharp rise in gasoline or oil prices. Pundits focus on the increases and cry foul if broad inflation gauges don’t confirm the price hikes at the pump. But it’s short-sighted to assume that a spike in energy prices will automatically lead to higher inflation overall.

It’s tempting to argue otherwise, especially now. Gasoline and crude oil have rallied sharply this year, creating what some might call a disconnect between tame inflation indexes overall and a critical price surge in the daily lives of consumers. For some folks, there’s more than numbers at work here; rather, it’s a conspiracy by the government to fool us into thinking that inflation is low when in fact it’s soaring. Gasoline prices, after all, are up roughly 50% this year. Surely, inflation can’t be docile.

But it’s almost always misguided to let energy prices guide your thinking on current and future inflation. Stripping out these prices (along with food prices) may seem like a dark plot by the government to mislead us, but in fact it’s just prudent economic modeling. Numerous research studies tell us why, but the most powerful explanation comes directly from history.

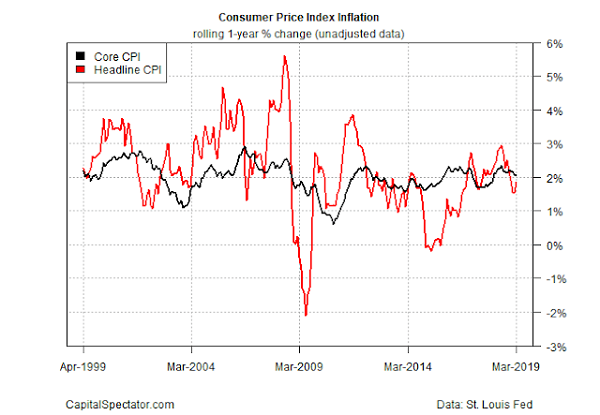

Consider how the headline measure of the Consumer Price Index compares with its core counterpart (which removes food and energy) on a rolling one-year percentage-change basis. As the chart below shows, headline inflation (red line) is a volatile beast, in part because energy and food prices bounce around by more than trivial degrees. Note, too, that the headline’s volatility tends to randomly fluctuate around the core data (black line). The obvious implication: if you’re looking for a robust measure of inflation’s trend, core is a better yardstick.

By contrast, letting headline CPI (i.e., food and energy prices) dominate your inflation analysis tends to lead you into analytical dead ends. The most extreme example in recent history: In 2008, when energy prices surged and so headline CPI flashed a warning sign that the inflationary apocalypse was near.

In reality, the energy bull market was having little if any influence on US inflation writ large. Indeed, core CPI was relatively stable in 2008. The attention of conspiracy theorists and inflation hawks, however, was firmly centered on headline inflation and the energy markets – a focus that ended up being deeply misleading… again.

But old habits die hard when it comes to looking for smoking guns in the inflation data. Some pundits are again pushing the runaway inflation narrative by claiming that this year’s run-up in the energy markets is a sign of things to come for the general price trend.

But core CPI disagrees, at least so far. This measure of inflation has been running below 2% at an annual rate for three months in a row through March – mildly below the Fed’s 2% inflation target. If this year’s rally in energy prices is an early warning that inflation’s trend is due for a hefty round of acceleration, there’s no sign of it in core CPI. That’s a reason to remain cautious that we’re on the cusp of upside breakout for prices overall.

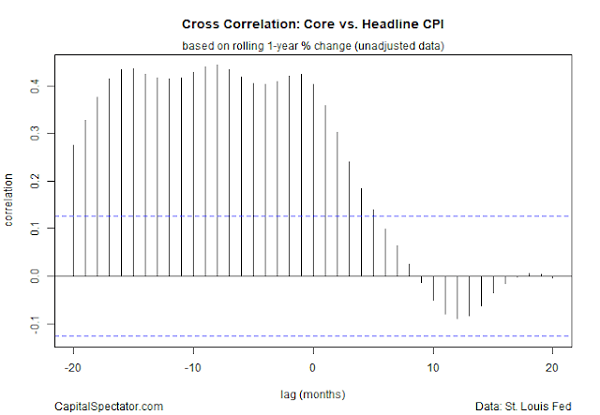

Core CPI is a better measure of inflation compared with headline CPI, but does core predict headline? To a degree, but we should be cautious on this front as well. Consider how a cross-correlation profile of core and headline CPI stack up.

The chart above tells us that core CPI has connection with future headline inflation, but only moderately so (as indicated by the roughly 0.4 readings at negative lags, which equates past core CPI values with future headline CPI). If core was perfectly correlated with future headline CPI, the readings would register 1.0.

Core CPI’s record on predicting headline CPI is mixed, at best. But as a general guide for monitoring the inflation trend in real time, core still beats headline by a wide margin.

Note: This article was contributed to EconMatters.com, courtesy of James Picerno, a veteran financial journalist since the early 1990s before becoming an independent writer/analyst/consultant in 2008. James is also the author of Dynamic Asset Allocation (Bloomberg Financial, 2010)and he writes at The Capital Speculator.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those of EconMatters.

Category: Energy